The personal harmonizes with the collective in this year’s Greek documentaries, the beating heart of the festival.

A report by Panagiota Stoltidou

From March 6 to March 16, 2025, Greece’s cinematic capital celebrated the 27th edition of its International Documentary Festival. Boasting 261 films and 72 global premieres across thirteen sections, this year’s tapestry of documentaries had a strong political focus, with Amber Fares’s Coexistence, My Ass! about Israeli comedian Noam Shuster-Eliassi’s advocation for peaceful coexistence between Israelis and Palestinians winning the International Competition Golden Alexander, TiDF’s top award and a distinction that immediately qualifies Fares’s film for Academy Awards consideration in the 2026 Documentary Feature category. The Silver Alexander was awarded to Jesse Short Bull and David France’s Free Leonard Peltier, the doc about the eponymous Native American activist who was falsely accused and imprisoned for the murder of two FBI agents in 1975, while the jurors also bestowed a special mention upon Weronika Mliczewska’s Child of Dust, the gorgeously shot cinéma vérité entry about Sang, one of the hundreds of thousands of children born during the Vietnam War to Vietnamese mothers and American soldiers, now searching for his long-gone father.

Honoring its continuous collaboration with Greek documentarians for yet another year, the 27th TiDF submitted a rental fee to all Greek films that were screened in its official selection. This included a total of 71 full-length and short documentaries across the three competition categories –International Competition, Newcomers and >>Film Forward– as well as in the Open Horizons, Platform+ and Special Screenings sections. From deeply personal stories and intimate portraits of remarkable personalities to shrewd examinations of Greek history’s darker aspects and fascinating excursions into both urban and rural vistas of contemporary Greece, these diverse movies joined forces to reaffirm the humanist power of documentary filmmaking. Below I highlight four of this year’s outstanding Greek entries.

Lo, dir. Thanassis Vassiliou

Premiering at the Newcomers Competition category and taking home this year’s Ekkomed Award for Greek Program Newcomer Director, Thanassis Vassiliou’s documentary essay is an accomplished debut that glows with philosophical insight. The film follows the director himself, now living in France, on a short trip back to Athens and the empty apartment of his childhood in the Galatsi neighborhood. It’s a year after his mother’s death, and Vassiliou must deal with his family’s troubled inheritance–to decide whether to keep the house he grew up in and accept the attendant debts, or sell it and move on. There is no easy answer to this dilemma. The apartment –once a haven filled with the sights, sounds and smells of family life– has now been reduced to a carcass, bare and silent. Is it still a home that Vassiliou can return to if it’s been stripped of all its familiar layers? In the Q&A session after the screening, the director called the present a symptom, something that you can gnaw at and tear off to reveal all the layers that lie hidden underneath it. Indeed: the film thrives on the conviction that the past can be tangibly felt and spoken to, even if it can’t speak back itself. In lyrical voiceover narration, Vassiliou addresses his deceased mother, lending added force to scenes of him, shot on an iPhone, rummaging through her remaining belongings in the abandoned flat. One of many talismans that his mother left behind and Vassiliou now encounters is a book, replete with notes and underlines. The apartment’s problematic legacy extends well beyond financial debts, and this found document becomes a crucial portal into the family’s complicated trajectory during the Greek Junta, spurring Vassiliou and his audience to a kaleidoscopic examination of events past that is at once deeply personal and necessarily collective. As archival footage from the colonels’ regime and old snapshots of family life are woven together into a tight audiovisual knot, public trauma bleeds into private loss. Yet the unearthing is not all pain. Vassiliou inflects his curiosity for the ambiguities of his family’s home with a defiant tenderness, and finally embraces the past for what it’s always been: “a mixture of sugar and sepsis.”

The One Who Hopes, dir. Stratis Chatzielenoudas

Part of the experimental >>Film Forward section of the festival, this documentary positions itself as a multifaceted meditation on the pragmatic possibility and the ethical relevance of hope in a post-apocalyptic age. It sets off with a terrestrial dawn, as the eponymously hopeful narrator and her AI companion arrive on Earth after a long intergalactic journey. In Chatzielenoudas’s unspecified dystopian future, language has gone extinct on most planets, and the silence brought on by its absence has slowly eradicated all living beings. Now, our narrator has reached language’s last remaining refuge with the hope of acquiring it and then reviving her lost world through it. Within this premise, The One Who Hopes proceeds to lend its attention to a diverse array of ideas and images, from canary singing competitions and the rural Greek community that seems to have mastered bird speech to artificial intelligence, the pressures of urbanity and the climate crisis. It’s an ambitious project, one that stretches the formal and methodological limits of documentary filmmaking at the same time as it asks demanding questions of itself and its audience. Is silence the end of life as we know it? And is there a point in beauty in a world that is bent on destroying itself? The film’s suggestion of a subterranean link between the loss of voice and planetary losses –the recurring human failure to communicate and the failure to preserve our environment– is intriguing, not least because it owes much of its clarity and force to editor Spyros Skandalos’s sophisticated collision of images, wherein the happy, loud pandemonium of birdsong in the shops of canary breeders often clashes with the eerie, imposing stillness of overflowing landfills. The One Who Hopes imbues its visual contradictions with both poetic and critical qualities and confidently straddles the line between hope and hopelessness.

Sculpted Souls, dir. Stavros Psyllakis

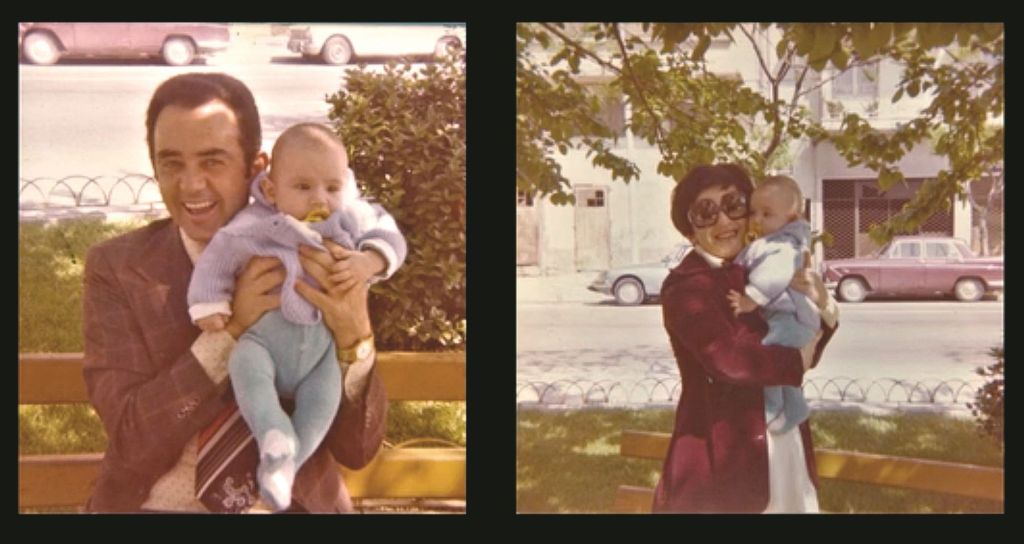

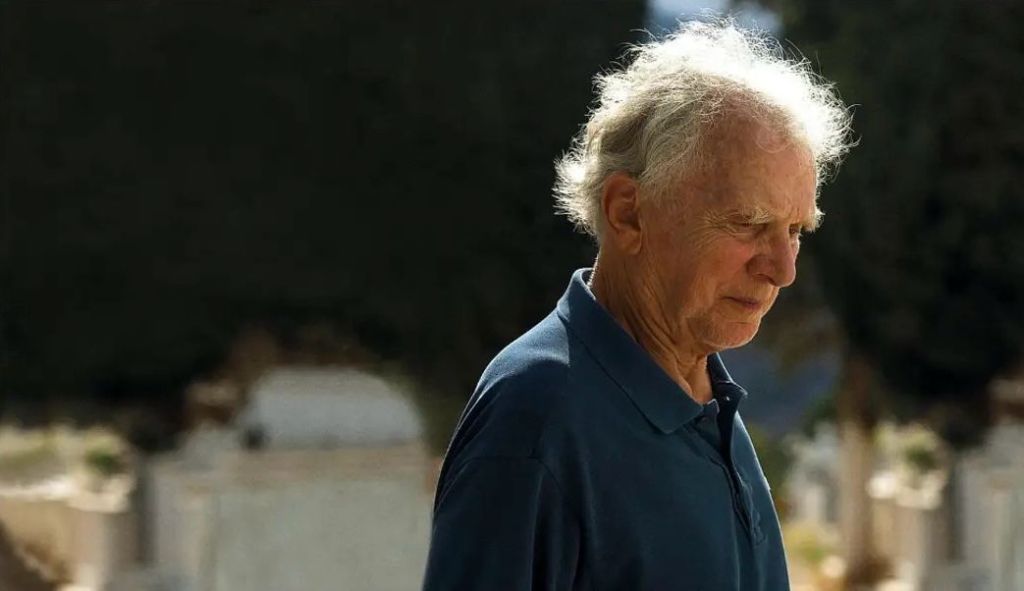

For 26 years, Swiss dentist Julien Grivel spent his annual leave in the Agia Varvara General Hospital in Athens, offering pro bono treatment to Hansenites–patients affected by Hansen’s disease, or what is commonly known as leprosy. An International Competition entry and the winner of this year’s Fipresci Award for Best Greek Documentary and the Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation Award, Psyllakis’s portrait of the dentist is based on the latter’s memoir “Greece, My Ithaca,” and opens on a wide shot of Grivel gazing at the sea and reflecting on cherished memories from his second home. Grivel’s kind eyes stand out first; his incredible, near-poetic command of the Greek language stands out second. The serene scene sets the tone for the remainder of Psyllakis’s film: Sculpted Souls is not another study of the history of leprosy in Greece, but a heartfelt, meticulous journey into the psychogeography of a truly remarkable man. With over 40 films to his name and an Honorary Golden Alexander Award from the Thessaloniki Film Festival, the acclaimed documentarian is renowned for penning and directing works about individual stories and outstanding personalities that he feels emotionally and creatively drawn to. Yet his films do not just bank on their unique subject matter to achieve their appeal but instead flesh out a sophisticated formal approach. Psyllakis’s latest is both an homage to Grivel and a beautiful testament to the director’s artistic sensibilities, combining assured cinematography with a memorable score and clever editing. The camera follows Grivel from up-close, lingering tenderly on his hands every now and then –a dentist’s hands marked by the passing of time and a life spent working and caring for others– while the montage combination of photographs from Grivel’s summers in 70s and 80s Greece and interview excerpts with Hansenite activists Manolis Fountoulakis and Epaminondas Remountakis conveys a succinct sense of both the private and the public aspects of Grivel’s connection to the country. Finally, Psyllakis’s documentary makes room for lyrical moments, too, as in the archival footage of Remoundakis smoking a cigarette with a deformed hand and looking straight at the camera. Shot in silent black-and-white, these scenes enter a visual dialogue with Forugh Farrokhzad’s masterful documentation of the Bababaghi Hospice leper colony in The House Is Black (1962), finding humanity and breathtaking beauty amidst all the suffering and isolation of the stigmatized disease.

Craftswomen, dir. Gabriella Gerolemou

“Where is the craftsman?”

Maria, Stavroula and Magda get this question a lot from first-time clients walking into their carpentry shop in downtown Athens. For some, it’s still unthinkable that women would take on woodworking jobs–or that they would do them well. Gerolemou’s Open Horizons entry follows the three longtime friends during their professional rite of passage, as they move from a shared basement workshop to their own carpentry shop in a new neighborhood and decide to make carpentry their main source of income. In the grand scheme of things, this choice might seem precarious. Apart from the daily misogynism that one is inevitably confronted with as a female worker in a male-dominated business, the job also comes with a volatile economic and professional outlook. For some time now, the demand for woodworkers in Greece has been dwindling, while it’s become near impossible to complete an apprenticeship in the field, let alone a higher education degree. Yet through Gerolemou’s affectionate lens, the girls’ gradual transition to professional carpenters is viewed more as an occasion worth celebrating than as a narrative seedbed for cutting commentary. It’s true, the film is not entirely without its critique of the status quo, either. But in addressing gender bias, or in challenging the capitalist ideal of a competitive workplace culture, the observational doc proceeds subtly, discreetly, never shifting the focus away from its fierce protagonists, their own impactful conversations and telling glances. After all, why would anyone want to shift the focus away from the carpenters? They are hilarious, brilliant, inspiring. They love what they do as much as they love each other, and this seeps into every aspect of their job, from the preparation of their designs to their interactions with clients and passersby. Craftswomen picks up on their solidarity wonderfully and makes it its centerpiece. It’s a watch as delightful and funny as Gerolemou’s subjects.

Leave a comment