Quiet and understated, this is a film that trades prison drama clichés for an authentic, emotionally resonant portrait of redemption through art.

A review by Ioanna Gousiopoulou

Based on the real story of the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program at Sing Sing Correctional Facility, Greg Kwedar’s profoundly humanist film arrives with something rarer in the crowded terrain of prison dramas, where high-stakes narratives often rely on violence, redemption arcs, or social outrage: quietness and calm. Sing Sing opposes melodrama and moralizing in favor of something more enduring—a tender yet sober look at the transformative power of performance and art. It cares more about the people making do inside the system than about the system itself.

The film wanders in and out of theater rehearsals, character exercises, and quiet times of introspection rather than following a straight, cause-and-effect storyline. The plot is not propelled by any one dramatic incident. Rather, the drama is inside the prison theater, in the slow, subtle flourishing of camaraderie, creative agency, and collective identity that takes place there. Some may find the pacing slow, almost meditative—yet this should be seen within the film’s broader aesthetic and even philosophical intent. This is a movie about becoming rather than arriving; about the ongoing process rather than the final product.

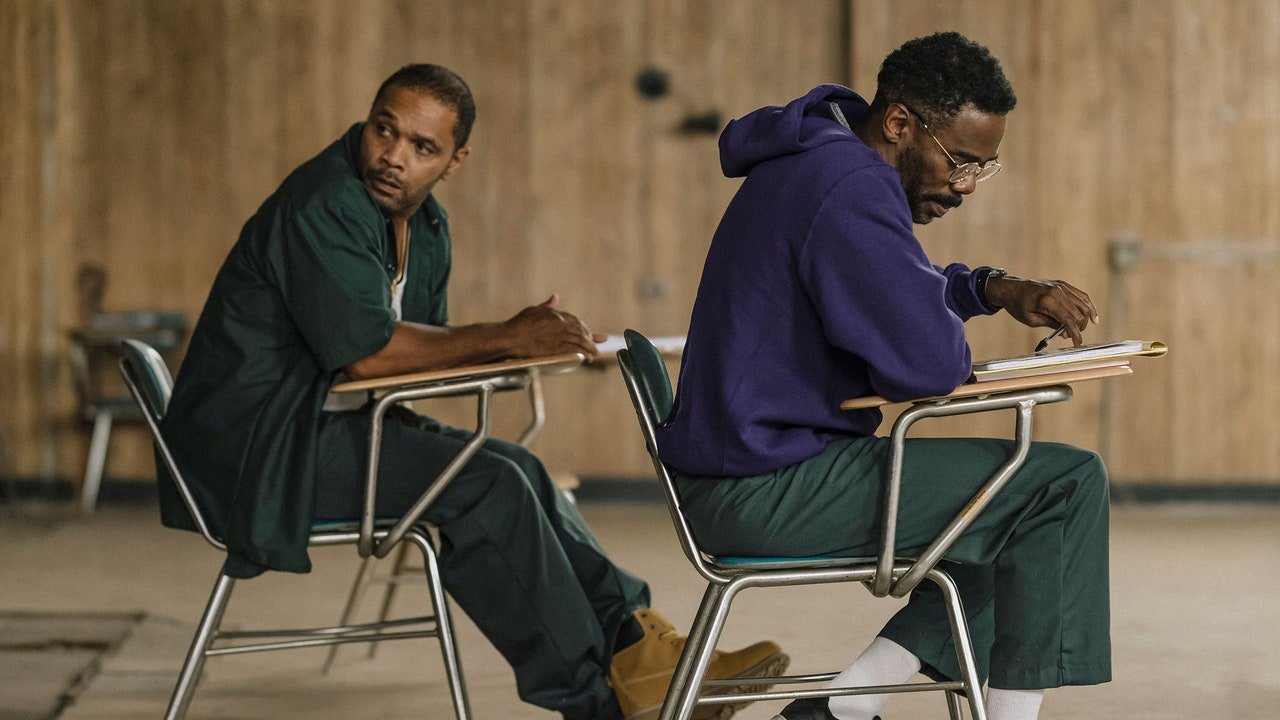

The movie’s visuals underscore its narrative concerns. Cinematographer Pat Scola works in soft, grainy textures that suggest intimacy instead of surveillance. Often depicted as a bleak, claustrophobic environment, the jail in Sing Sing figures as something more nuanced. Yes, it’s still a confining space; but Kwedar and Scola bring out the light between the walls rather than their concrete harshness. Sensory detail is highlighted: the echo of voices in rehearsal, the synchronized breathing during warm-up drills, the scratch of pencil on script pages.

The incomparable Colman Domingo drives the film as John “Divine G” Whitfield, a wrongfully accused convict who has found unusual atonement as the theater troupe’s leader. Domingo’s performance is both measured and moving. He does not gesture broadly in pain. Rather, his character’s strength derives from a subtlety of emotion—his soft voice when guiding others, or the way his face registers the tiniest tremors of hope and despair. Domingo lets the truth radiate reservedly; John is a man who has learned to survive through disciplined grace.

The rest of the cast also merits special mention. Many of the on-screen characters are not played by professional actors but by actual RTA program alumni, men who served time and now return to share their side of the story. First among them is Clarence Maclin, who in portraying a fictionalized version of himself does not seem to be acting at all, delivering emotional truth through lived experience. His casting and performance can be seen as an instance of the film’s refusal to sensationalize its topic. In Kwedar’s carefully crafted universe, the backstories and crimes of these convicts-turned-actors are neither a narrative nor a moral compass. We are asked to view the characters for who they are now, indeed, for who they have chosen to become—in performance, in rehearsal, in conversation. The stage is made into a vehicle for reshaping identity, and succeeds in reminding us how the human need for creative expression perseveres even within systems meant to dehumanize.

It would be easy, perhaps, to brush off Sing Sing as a feel-good movie, but that would flatten its complexity. There is no great catharsis or climactic triumph. The characters’ experience of freedom is fleeting and brittle. And yet while it lasts, it’s authentic. In place of neat answers and happy endings, we are subtly brought to revolutionize our understanding of personhood as a process that is not trapped in the past but opens, constantly, onto the future, through art and connection. Ultimately, Sing Sing celebrates the messiness inherent to reclaiming one’s narrative—the hard facts of one’s life together with the persistent traces of one’s humanity. It’s a film that chooses to complexify and remember in a world trained to label and forget.

Leave a comment