Honoring the festival’s commitment to emerging talent from Greece and beyond, artistic director Yorgos Angelopoulos’ first term in office yielded a lineup as thematically diverse as it was unified in its solidarity politics.

A report by Panagiota Stoltidou

Last weekend, Greece’s leading short film festival closed off its 48th edition amidst a packed auditorium, in what proved to be one of the institution’s most memorable —and eventful— awards ceremonies to date. With a program spanning 223 films from 49 countries and 146 national premieres across seven competition categories, there was plenty to celebrate. There was also plenty to grieve. Before the inaugural speeches, a large group of filmmakers and industry professionals got up on stage and raised the Palestinian flag, as actor Antonis Tsiotsiopoulos read a statement of support for Oxygen, the Greek vessel that was to join the Global Sumud Flotilla headed to Gaza that same evening. Many of this year’s winners took a moment to condemn the genocide of the Palestinian people, while various awards were bestowed upon Palestinian productions, with Phoebe Cottam’s When You Were Young Were You Afraid of the Moon? (2025), the moving story of a family of four strong women living amidst immense turmoil in Gaza and beyond, taking home the Fipresci Award for Best Film in the International Competition. From jury members and film critics to the casts and crews of this year’s winning productions, a range of speakers also used the stage as a platform to confront Deputy Minister of Culture Iasonas Fotilas, seated in the front row, about the Greek government’s chronic failure to meet the industry’s basic financial and structural needs—a shortcoming that weighs especially heavily on the often-overlooked short film format. Fotilas wasted no time firing back, but the heated exchanges only fueled the evening’s activist energy, fittingly capping a festival edition brimming with politically charged films. Here’s a closer look at my top four picks from the National Competition of the 48th DISFF.

Noi (2025), dir. Neritan Zinxhiria

High up in the Epirus mountains, a horse kills a boy. We never learn much about what happened; but the death casts a visible shadow over the lives of the horse herder community that the boy’s left behind. None is more affected than his younger brother, whose grief is pierced by a moral dilemma: should he avenge the death or forgive? Taking home this year’s Golden Dionysus, the DISFF’s top award and a ticket to the 98th Academy Awards race for Best International Short Film, Neritan Zinxhiria’s latest follows its teen protagonist along a path of emotional reconciliation. It’s a tender film, and one that relies on images over dialogue to tell its tale of subtle transformation. From expansive vistas of snowcapped valleys to fleeting minutiae of grief-stricken faces, Christina Moumouri’s breathtaking shots are rendered with a humanist curiosity. The attention they are given is serious and sustained, and yet the camera never once lingers uncomfortably, nor does it pull its various subjects —humans, horses, mountains— into an interpretive whirlwind. In a similar manner, Noi’s repeated flights into fantasy are not products of aesthetic imposition but of meticulous psychological excavation, and they form an integral, if hidden, element of this austere alpine reality. It’s Zinxhiria’s crowning achievement that the symbolism of his work is not forced upon its lush, enigmatic images but rather recovered from them—a world contained within another world, leading its own life under all the snow. Noi unearths this rich world with great care and nuance, and what it finds is nothing short of miraculous.

Magdalena Hausen: Frozen in Time (2024), dir. Yannis Karpouzis

The film gets its intriguing title from the Frozen Time Laboratory, the photography lab that German artist and activist Magdalena Hausen attended under Andreas Weder in the Academy of the Arts in 1970s West Berlin. It was during that traineeship that Hausen’s passion for the medium became serious, launching her into the intensive pursuit of a method that would help her achieve what her long-gone father, an engineer-turned-photographer, never could: freeze time, that is, capture something as fleeting as the wind. Magdalena Hausen: Frozen in Time is the eponymous artist’s existential quest to carve out an identity through a deep dive into the private archives of her past. This is a task no less Sisyphean than taking a photograph of the wind, we soon find out. Photographs are, after all, incomplete memories of a self that is now lost forever, as an elderly Hausen herself confides to us in the beginning of the voiceover narration. Equal parts personal testimony and historical essay, Yannis Karpouzis’ hybrid documentary short unfolds as a series of still, grainy images that map out the visual cartography of a life steeped in loss, longing and continual change. Drenched in historical references and yet somehow glowing with an otherworldly light, this richly textured montage of images has something of the mythical staging that belies all forms of memory-making. The deft stylization becomes a poignant reminder that remembering is always also reconstructing—that the past is an artifice of the present, not unlike fiction. The recipient of the Special Mention and Best Editing Awards of the National Competition section, Magdalena Hausen spins the pleasures of a rhyme scheme, keeping an elegant balance between what returns and what moves forward; time and again, the photographer encounters people, objects and moods in variations subtle enough to contain an essence of the past and yet always also consequential enough to herald a future. In the uncanny echo chamber of Hausen’s life, the wind persists as a paradoxical constant, if only for the fact that it is constantly fleeting. The other constant is Hausen herself, of course, though perhaps her identity is no less elusive.

Pirateland (2025), dir. Stavros Petropoulos

The setting is Gramvousa, on the island of Crete. It’s the end of the tourist season and prospects are looking grim for “Pirate’s Land”, the family-owned B&B run by local fisherman Manos (Kostas Koronaios). Only child Tasos (Asteris Rimagmos) offers an all-too-easy outlet for his father’s frustration at their dwindling clientele; impromptu cardboard sign held gloomily above his head, he’s hardly a poster boy for the Greek hospitality he’s selling from his post on the port. Unlike Manos, though, Tasos seems to enjoy the downtime. An early scene sees him returning home on foot after another unsuccessful shift, blasting music through noise-canceling headphones and dancing ecstatically in the middle of the empty road. Yet even he can’t tune out the world forever. Shaking Tasos out of his daze is the sudden arrival of a Norwegian family, who look to spend some quiet days on the island sequestered from the big tourist crowds. What starts as a felicitous opportunity for the Greek family drifts into muddy waters when their guests request what they term the “authentic experience”—they’ve heard there were pirates in the area once, and wouldn’t it be great if Manos and Tasos were to channel their savage ancestors and play at abducting them? It’d all be harmless enactment, of course, and there’s a generous extra payment involved. Manos is in no position to refuse, and the plot’s slow descent into absurdity, elegantly written by Yorgos Teltzidis, finds dark humor in the horrible depths of our estrangement from our dwelling places, and in the theater of self-exoticization dictated by the relentless machine of the tourist industry. As the games turn increasingly precarious, forcing Manos and Tasos into an unlikely alliance, Pirateland also digs up the forgotten tenderness of a fraught relationship. It’s a smart film, beautifully shot and acted, and one that delivers a fresh approach to a pressing matter.

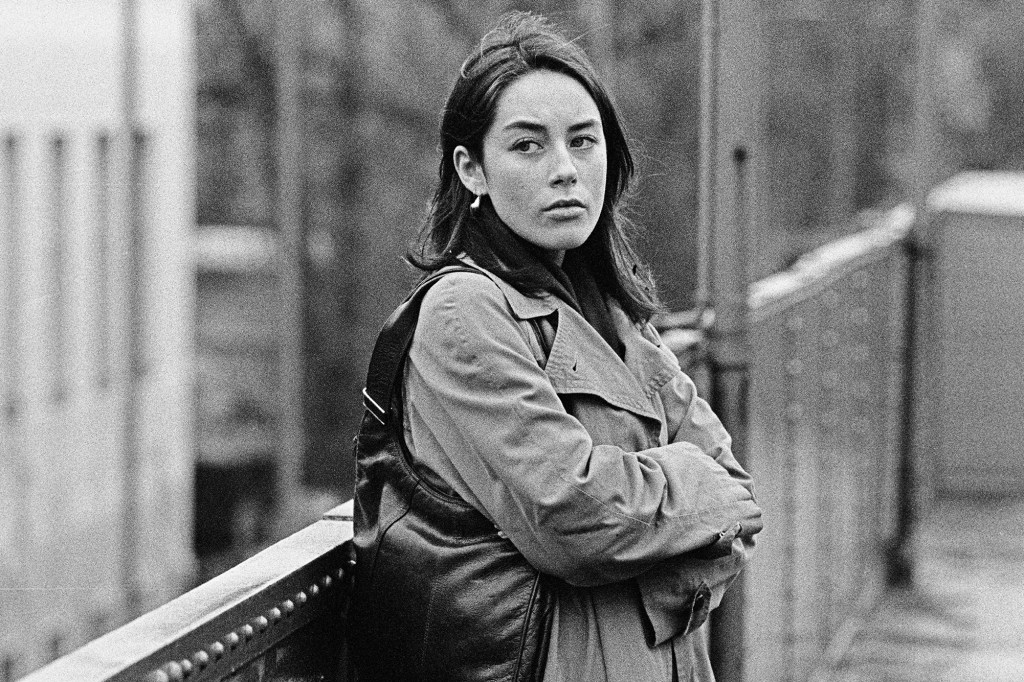

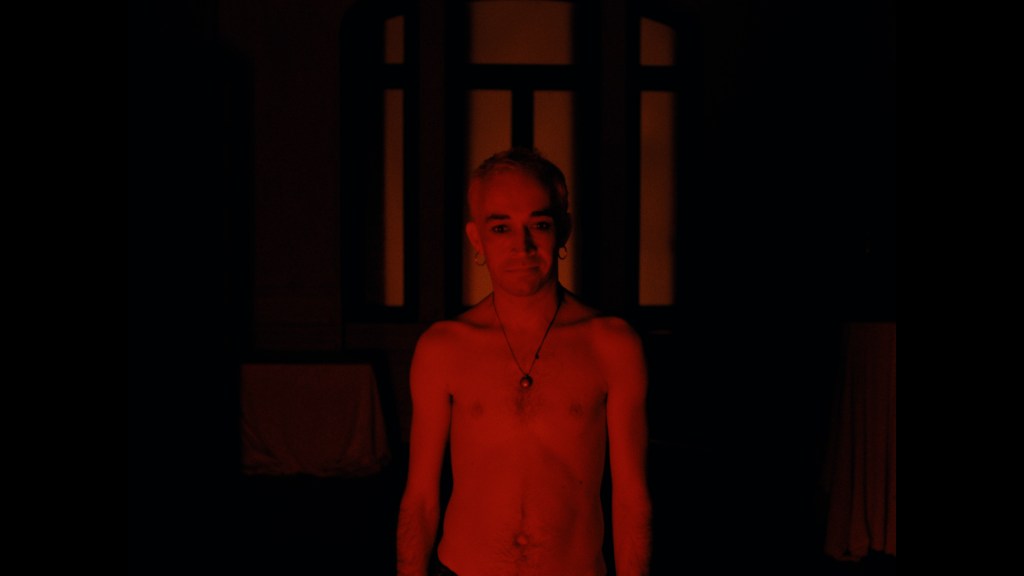

He Who Once Was (2025), dir. Kostis Theodosopoulos

A haunting tale about urban loneliness and queer identity, Kostis Theodosopoulos’ second short took the festival by storm—it won Best Director, Best Actor, Best Makeup Design and the Drama Queer Award of the National Competition section. The film follows a drag performer (Aris Balis, who also cowrote the script) working sold-out gigs in a basement bar and leading a hidden nocturnal life as a blood-thirsty vampire. For someone who’s been alive since the 18th century, few things can still inspire surprise, and one’s day-to-day is lived best when it’s punctuated by habit. So our hero’s worked out a successful rotation of entertaining sketches; he’s determined how to pick his victims during shows, and how to gorge on their necks in the privacy of dark alleyways; time and again, the early hours of the morning find him disposing of their bloodless bodies in the nearby shipyard. He who once was invariably spends the rest of his time splayed out on his floor mattress staring at the ceiling, his eyes doomed to remain open and unblinking for eternity. Yet everything changes after he meets the awkward, unassuming Petros (Konstantinos Avarikiotis), a middle-aged audience member whom he initially dismisses for not fitting his victim profile. Could this stranger become a trusted companion in his interminable journey? Unfolding with the accelerating drama of a tightly constructed short story, Theodosopoulos’ vampire myth walks a delicious line between neo-noir and erotic thriller to conjure a world that is at once ruthlessly morbid and deeply felt. At the heart of it all is Balis’ incomparable performance, engineering our honest empathy for the fate of a man suspended in his search for a self he can live with, and for someone to understand him.

Leave a comment